In 1860, Ypsilanti made use of the old Presbyterian Church on Pearson (where Owen Business College now stands) for the education of the City’s black children. The old building was being used by the congregation of the Second Baptist Church, then led by H.P. Jacobs, a man who escaped bondage in Missouri with his family by writing their own passes and who prized education. He would go on to found the Natchez Seminary in Mississippi after the Civil War. The Seminary was the first public school in Mississippi and the forerunner of Jackson State University. It is likely that Jacobs helped lead the effort to open education to his community.

The old First Ward School is among the most historic buildings associated with the Ypsilanti’s history and is deserving of recognition and preservation. The Adams Street building was constructed during the Civil War, in 1864, specifically to educate Ypsilanti’s black children. Generations of children were taught there, mostly by black teachers. The first teacher, John Hall, was a black man who also plied a trade as a cooper (barrel maker).

Isaac Burdine, a Regional Grand Master of the Michigan Prince Hall Masons, lead the First Ward School, and much of Ypsilanti civic life, from shortly after the school opened until his departure for Indiana in 1877. Other teachers included Susie Gorton, Mrs. Alexander, who taught for over a decade, and eventually Bernice Kersey, the last teacher of the school before it closed. She was a member of the Kersey family, prominent in Ypsilanti for generations, who were plaintiffs in the School’s desegregation case.

First Ward school teachers on the steps of the school in 1918. Starting at the left is Bernice Kersey, Ruth Sykes Penn and St. Clair Price. YHS.

School children populations around 1900.

The Ypsilanti school census shows a falling off in school population in that city. In 1891 the school population was 1,773, in 1892 it was 1,684, and in 1873 it is 1,607, a falling off of 166 in two years. The falling off of the white school population is 106 and of the colored 60. The colored school population now numbers 131.

Ann Arbor Argus. September 15 1893.

The total number of children of school age in Ypsilanti this year is 1,772, an even hundred more than attended last year. Of this number 1,609 are white and 163 colored.

Ann Arbor Argus. September 10 1897.

Ypsilanti has 1778 children of school age of which 155 are colored, a gain of three colored children and 10 white over last year.

Ann Arbor Argus. September 16 1898.

The school, the oldest surviving structure associated the Ypsilanti’s black community, has played host to innumerable political and community meetings from its earliest days. It was a center of black life and a cornerstone of the community which grew up around it. In the 1870s, the pro-Reconstruction Grant Clubs met here, the first explicitly black political organizations in the City. A number of those activities are mentioned in the newspapers section.

The short sketch below was written in 1907 and takes a look at long-time teacher. and AME member, Anna Chalmers Alexander (pictured above), Written for a directory of important black leaders, the editor made an exception for Mrs. Alexander, who was white. Anna lived at nearby 109 Buffalo St. with her husband, a conductor on the Michigan Central, for many years. Widowed in 1913, she remarried in 1919 and was tragically killed when the car she was travelling in with her husband was struck by an interurban on the eastside of Ypsilanti in October of that year.

Mrs. Anna Chalmers Alexander

Mrs. Anna Alexander is a white school teacher of this city. But the author is forced to speak of her because of the noble work she has done for the colored people in Ypsilanti and because of the high esteem they have for her and the honor they wish to confer on her through the medium of this book. The sentiment of the colored people style her as one of the noblest and most generous women of the age.

She has been very beneficial to the colored people and was very active in bringing about their prosperity, which is in evidence there, and is looked upon by the school children as a “‘Lady Bountiful.” The colored people are aware of Mr. Alexender’s good qualities and credit her with honor and reverence for them. She is one that is planning and working for the advancement of the colored race and advocates their justice. Mrs. Alexander has contributed largely to the colored churches of Ypsilanti, and is of great help to the pastors of those churches. Many thinly clad children have been clothed by her. It did not matter to her whether the children were black or white. Her gentle nature has made her greatly loved by all the children. Her greatest joy is to inspire children to live noble lives. The author was deeply impressed by Mrs. Alexander’s charitable nature and earnestness to keep any one she could.

He never saw a school room filled with brighter faced children in his life. Their teacher instructed them to put aside their books and listen to an address given them by the author. The school is of good discipline and under the control of an extraordinary good teacher.

Buck, D. D.. The progression of the race in the United States and Canada treating of the great advancement of the colored race. Chicago: Atwell Print. and Binding Co.,1907.

What began as a statement of support for black residents by the City during the Civil War had become a symbol of the segregation that had become dominant by the early 1900s. The school taught exclusively black children through grade six, at which point they went to integrated City schools. Underfunded, overcrowded and in disrepair, the city came under pressure from the community to address the problem.

Robert W. Bagnall. NAACP Organizer around the time he helped to form the Ypsilanti Branch of the NAACP. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

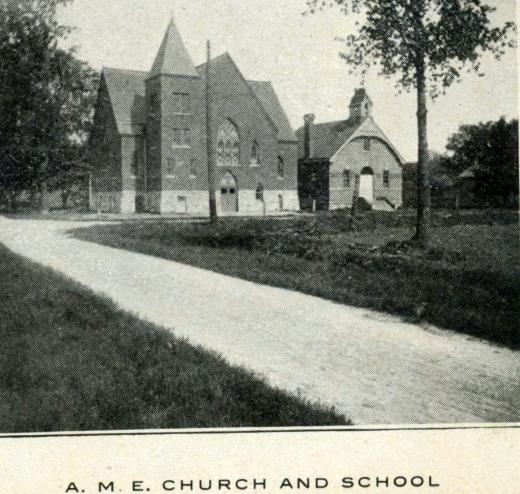

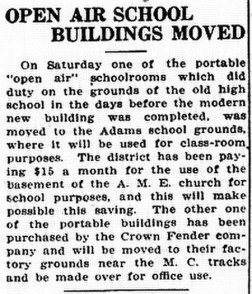

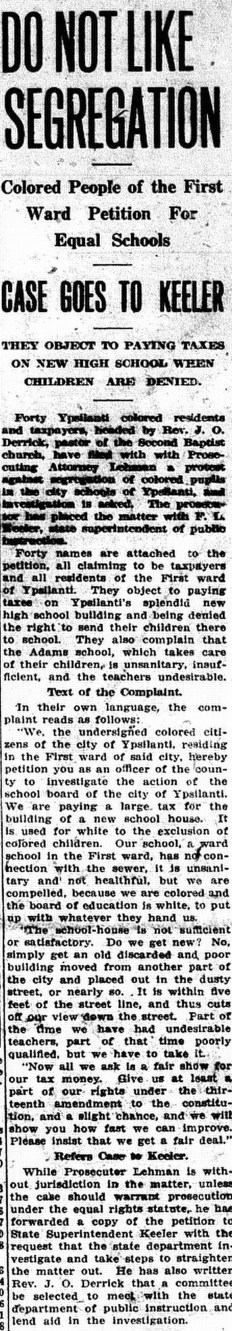

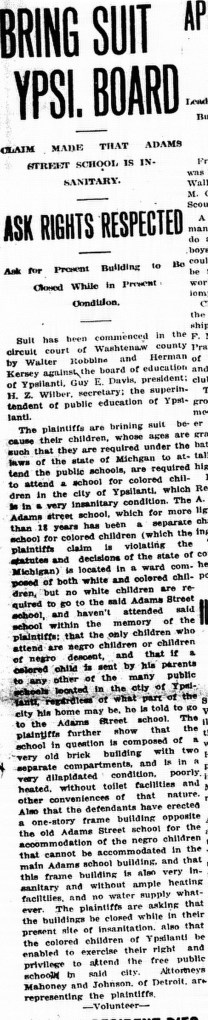

The struggle began in 1916 after a dilapidated frame structure was moved across the street from the school to accommodate the overflow of students, while the city was busy building its new high school, located on Cross Street. The school on South Adams had no indoor plumbing and was heated by an antiquated stove that emitted more smoke than heat, appropriately called ‘Smokey’. A petition to the local prosecuting attorney in August, 1916 was signed by forty residents of the First Ward demanding that their rights, as citizens and taxpayers, be respected. The full text of the petition, a milestone in Ypsilanti history, can be viewed in the article below.

A bond was proposed by the voted down, with support of the black community, that would have rehabilitated the school while increasing the grades taught, effectively expanding segregation under the guise of aiding the school. The community was adamant; it wanted an end to segregation. Robert W. Bagnall, then Great Lakes Organizer of the NAACP helped to establish Ypsilanti’s NAACP branch in 1918. This early NAACP chapter, with fifty members, was spearheaded by local activist William Clay, along with Walter Robbins and the Kersey family (Bernice Kersey was then the First Ward teacher) to fight the move. Robbins and Herman Kersey were chosen by the community to represent them as plaintiffs in the case.

Detroit attorney and NAACP leader Charles Mahoney, who later worked on the Ossian Sweet Case, led the legal challenge. The bond initiative was also opposed at the ballot box and defeated. The case was won in Judge Sample’s Circuit Court and Ypsilanti schools were formally desegregated in May, 1919. The First Ward school closed that year.

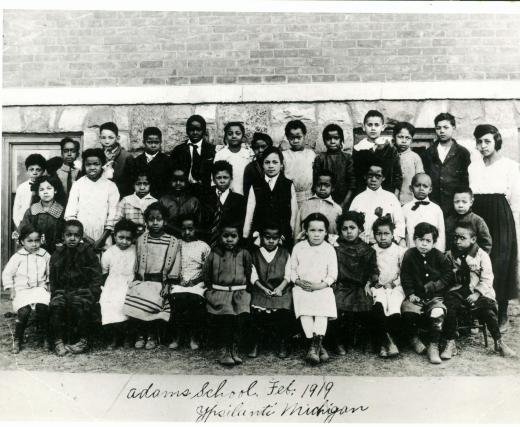

Photo taken during desegregation case. This would prove to be the last class taught at the school. Teacher is Bernice Kersey. Ypsilanti Historical Society.

During the late 1910s, the NAACP challenged discrimination in the City. A case was brought by Mahoney on behalf of Marshall Scott against the Forum Theater of 226 West Michigan Avenue. The theater refused to sell blacks floor seats to events. The NAACP also challenged the lack of black jurors on local trials during this time. The NAACP went into decline in the 1920s and 30s, only to be revived in the housing crisis of the 1940s. The chapter was active during the 1960s and continues to this day.

The old First Ward School is now the New Jerusalem Church.

Below are several historic articles which discuss the school over the years. The first is from the NAACP’s The Crisis, edited by W.E.B DuBois, published in June 1918 and written by NAACP organizer Robert Bagnall. Later, a 1919 report from The American School Board Journal. Photos from the Ypsilanti press can be enlarged by clicking on them.

The Ypsilanti School Decision

In Ypsilanti, Mich., there had existed a colored school for forty years. All Negro children attended this school to the sixth grade. The building was most unsanitary and its equipment inferior. Recently a bond issue was proposed and most of the Negro voters were disposed to favor it, for it was to provide a $40,000 Negro school. The fact that this school was to include all the grades of the grammar school and eventually of the high school, making segregation in education complete, did not seem to affect them.

For forty years the whites had imposed a Negro school on them, and it was useless and vain to rebel. The writer invited himself to a meeting held to dis cuss the bond issue and took with him a brilliant young attorney of Detroit, Charles H. Mahoney, who is intensely interested in his people. The two of us tried with all our might to get them to vote down the bond issue, to organize a branch of the Association, and to take the case of a separate school into court. Mr. Mahoney offered his services as attorney free of charge. We thought that we had failed, but not only did they vote down the bond issue, but they requested the District Organizer to come and establish a branch of the Association, and the first thing the branch did was to accept Mr. Mahoney’s offer.

A short while ago, the case was tried and Mr. Mahoney’s clients were awarded the decision that this Negro school was both unsanitary and illegal and must be closed as such. It was my pleasure to be present a few nights later when this branch presented Mr. Mahoney with a purse of eighty-five dollars in appreciation of his services.

Robert Bagnall, The Crisis, Volumes 15-18 National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, 1917.

Ypsilanti’s Segregated School to Close

The city of Ypsilanti has a colored population of approximately eight hundred persons who live in a segregated section of the first ward. In this ward there is a school population of 431 of whom two hundred are colored children. The Adams Street School which came into existence several years ago, has continued to exist thru the desire of the white population and by sufferance of the colored race. During the past few years efforts had been made by the school authorities to make the school function in the life of the colored population and some opposition had arisen. The trouble culminated last summer when the board submitted a proposition to the voters of the district for a new building to serve the school and the community. Led on by outside influence, the colored people voted against the proposition which resulted in the failure of the project and the subsequent litigation in the court.

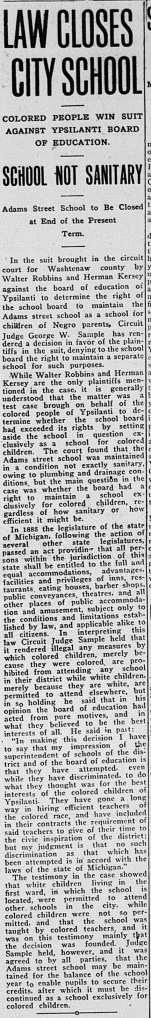

In the suit brought by Walter Robbins and Herman Kersey against the board, the plaintiffs contended that the Adams School was being maintained by the board in an insanitary condition, and that it was without proper sewage, light and heat. They also contended that the school was conducted as a separate school for the colored children of the surrounding district who had not attained a higher grade than the sixth.

In making its decision, the court acknowledged that sufficient evidence had been submitted to show that the school in its present condition was insanitary but it also pointed out that the board had done what it thought best for the colored children and that it had gone a long way in hiring efficient teachers and in improving the civic conditions of the community.

The important question, in the court’s judgment, was whether the school was being conducted by the board for the children of negro parents of the ward In such a way as to compel the children, because they are colored, to attend the school, and at the same time to permit white children of the district to attend outside schools.

The court maintained that the maintenance of the school was an act of discrimination against the colored children and that in view of the provisions of the Michigan law, it was a violation of the common law of the state and of the statutes of the state. The court cited’ a number of important decisions from Supreme Court cases to support its contention that all residents of a state have an equal right to attend any school and that they may not be discriminated against because of race or color.

The court in rendering its decision ordered that the school be kept open for the remainder of the present term in order that the pupils might receive the proper credits and that at the end of that time it be discontinued.

The American School Board Journal, Volumes 58-59, National School Boards Association, 1919.

Dozens of original scanned newspaper articles from 1865 to 1920 are located in the First Ward School Newspaper Archive.

For more photos of nineteenth century Ypsilanti school children see this page.

What an informative website this is! I had no knowledge of this anti-discrimination court decision, from Ypsilanti, in 1919! Bravo for revealing all this important history.

Thanks, Mark. I hope to have a few more stories from the case posted soon.